Doktorand: Rune Frandsen

Dieses vom SNF geförderte Forschungsprojekt wird federführend vom Institut für Landschaft und Urbane Studien (LUS), Professur Günther Vogt, ETH Zürich geführt. Prof. Dr. Silke Langenberg ist Co-Referentin der Dissertation.

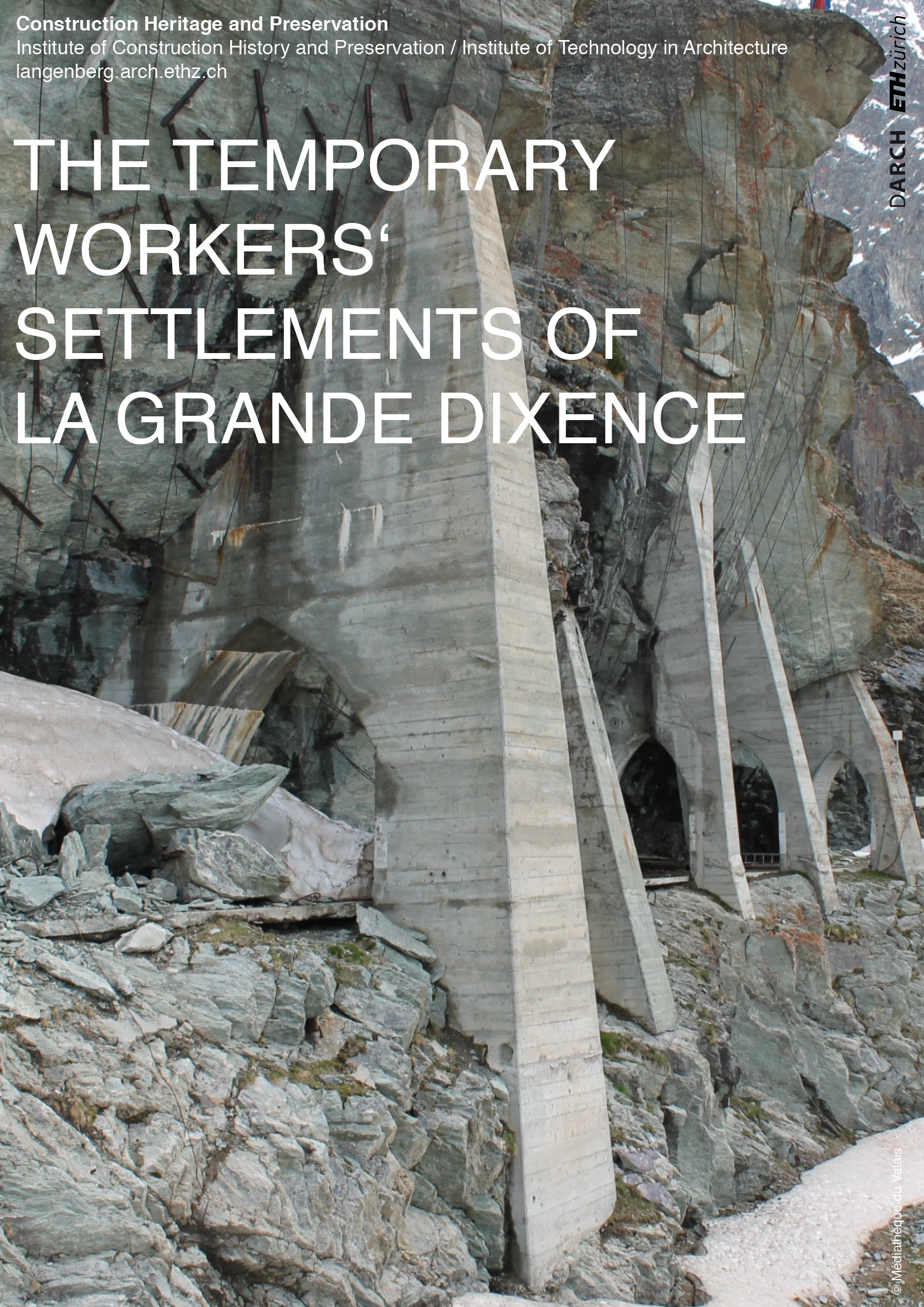

In 1945, The National Office for Water Management of Switzerland released a study listing the remaining opportunities for hydropower within the Rhône River watershed in Valais. It sparked a massive campaign of dam building in this mountainous region which was to last for the following three decades. Most of this hydroelectric infrastructure is remote and underground, which means that it is less visible and therefore absent in representations of the Alpine space. In the same vein, its invisibility also pushes the thousands of workers employed for its construction out of the spotlight. This dissertation focuses on one case study, the construction period of the Grande-Dixence (1950–1965), and documents what will be defined as thesecondary infrastructure: all the infrastructure necessary to build this (primary) hydroelectric network. This includes the arteries for material transport and its roads, tunnels, bridges, and cable-cars; the workers building the dam and digging the tunnels, the networks for the procurement of this labor, and the temporary settlements in which the workers were housed.

The chosen method, archival research, yields two conclusions. First, the study of the accomodation provided to the workers, of their working schedules and wages, and of the services provided within the temporary settlements show that the space produced by this secondary infrastructure was a space of discipline. The project of transforming the alpine landscapes for resource extraction was entangled with a process of regimentation of the minds and bodies of the workers. Second, drawing a portrait of both the population that these constructions relied on—in a large proportion Italian “guest-workers”—and of the construction details of the barrack-huts in which these workers were housed show that, rather than being temporary, these construction sites were mobile. This provides important incentives to reconceptualize the building industry’s relation to labor, where ephemerality is too often used to legitimize poor living conditions. As an outlook, field studies document the remains of this secondary infrastructure, what Peter van Wyck has called the territorial archive, presenting it as the built heritage of the contributors to the construction of the Swiss hydroelectric infrastructure.